Evolution of Android Binary Hardening

How has Google’s Android platform evolved with regards to build safey?

Evolution of Android Binary Hardening

Google’s Android is, hands down, the leading platform for mobile users. With more than 75% of the market, it is perhaps the single most important platform when it comes to end-user security.

As a Linux variant, Android supports all of the binary hardening features you’d expect, from kernel-provided defenses like ASLR and DEP, to compiler features such as stack guards.

In our previous study of Linux-based IoT devices, we found a widespread disregard for these features: some were essentially unused, some were used with coin-toss odds.

So how does the premier mobile platform compare?

What we found was encouraging:

- Over the life cycle of Android, binary hardening has improved drastically

- Android has consistently improved and been reasonably consistent with applying hardening

- Among the hardening features we studied,

FORTIFY_SOURCE(whose utilization drops after android 6.0.1) was the only one whose utilization could be drastically improved.

The corpus

For this study, we downloaded major and minor versions of the factory images of Android from https://developers.google.com/android/images, mostly for the Nexus/Pixel flagship devices. We then extracted the filesystems and processed every binary or library with our analysis engine.

In all our corpus includes:

- 24 Android Releases

- 14358 binaries

- Data from 2009-05-01 to 2019-09-01

- Coverage of major & minor versions spanning 1.5.0 to 10.0.0

(Note: We did trim out .odex and .oat files because they are non-standard ELF files handled by different loaders than the Android / Linux kernel.)

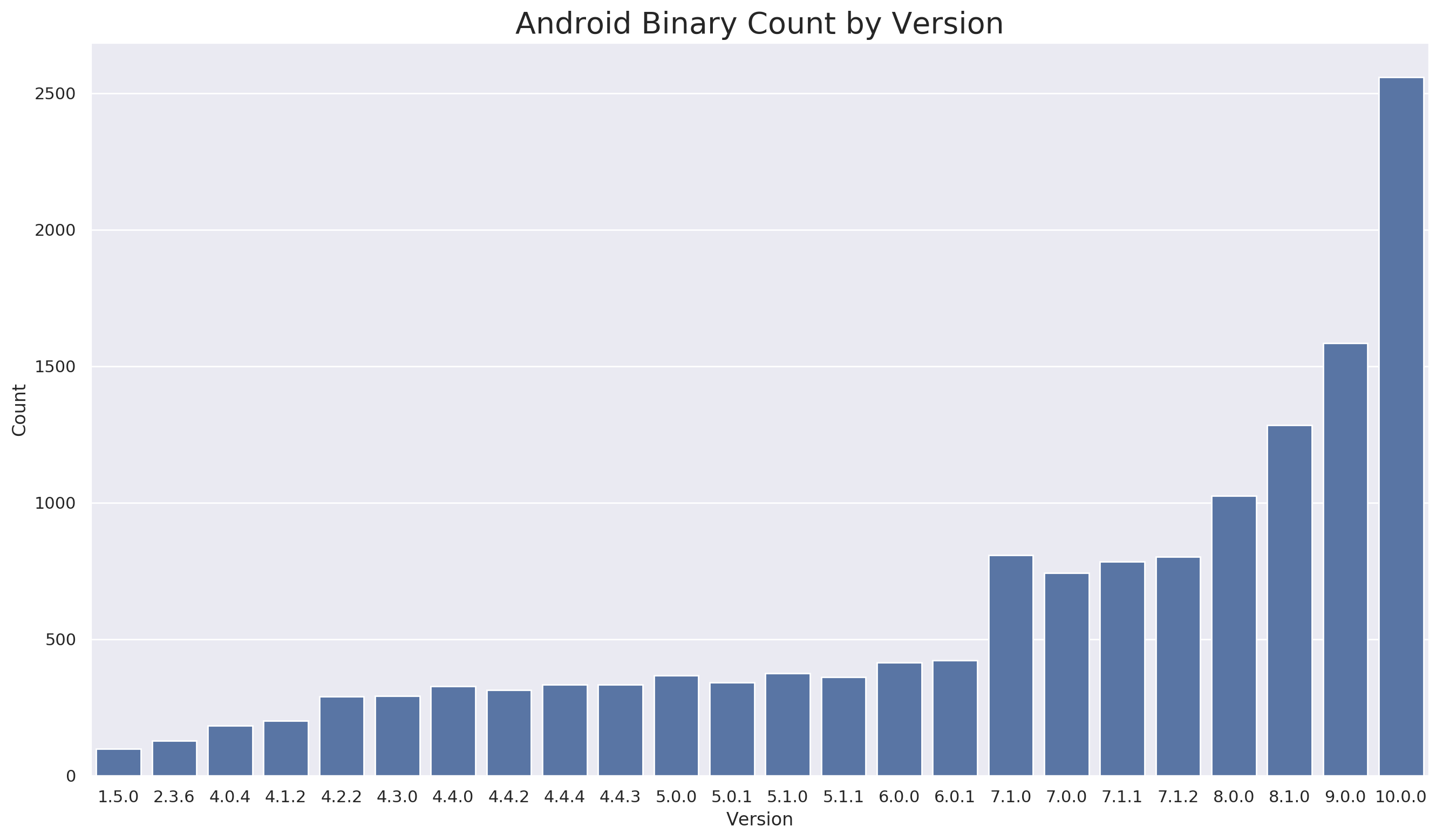

Firmware Size and Architecture

We begin by looking at how the Android platform has grown over time. The following graph shows the number of binaries we recovered from each version of android:

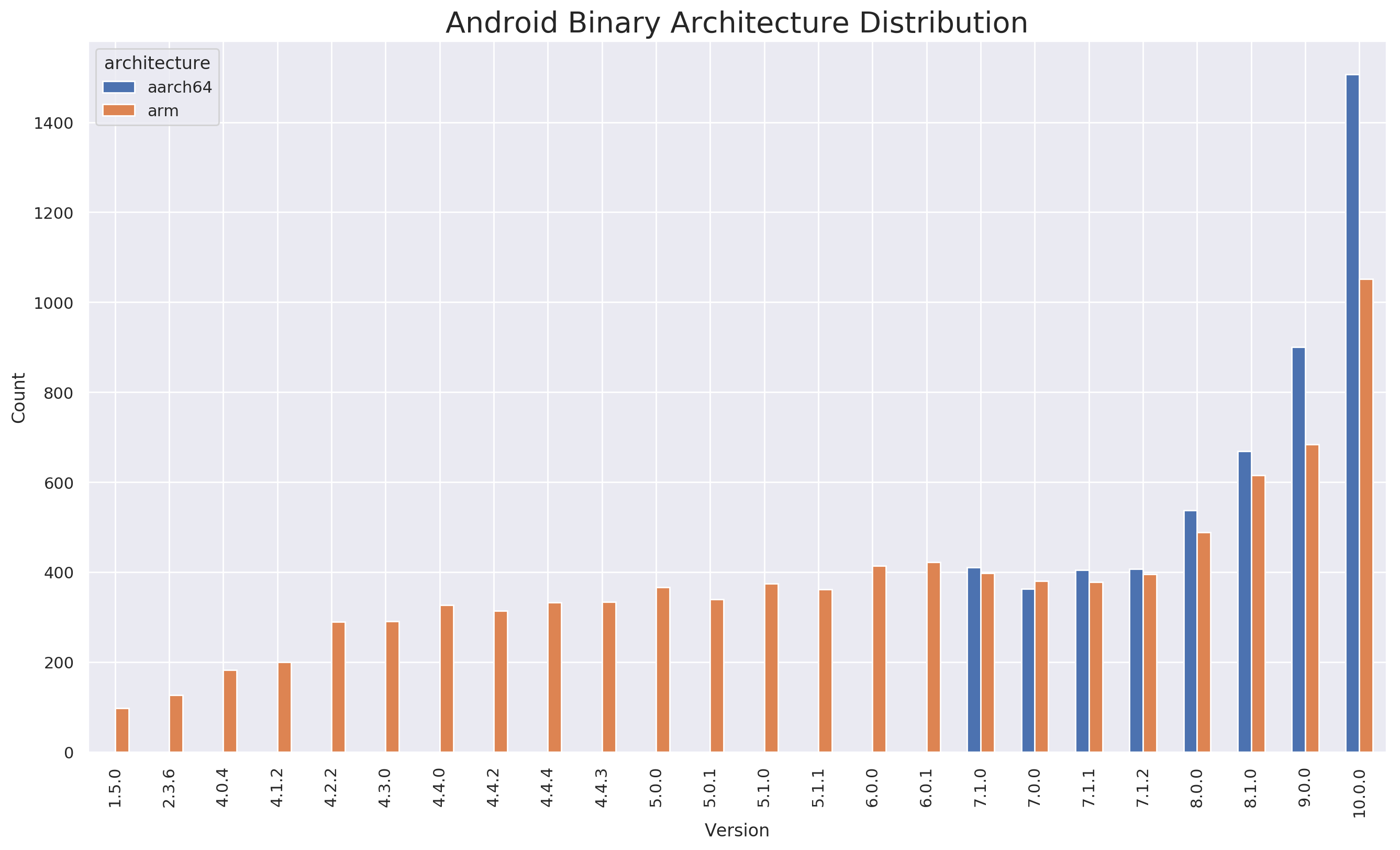

The following graph shows the same data, but tracks aarch64 and arm separately:

Average Scores Per Release

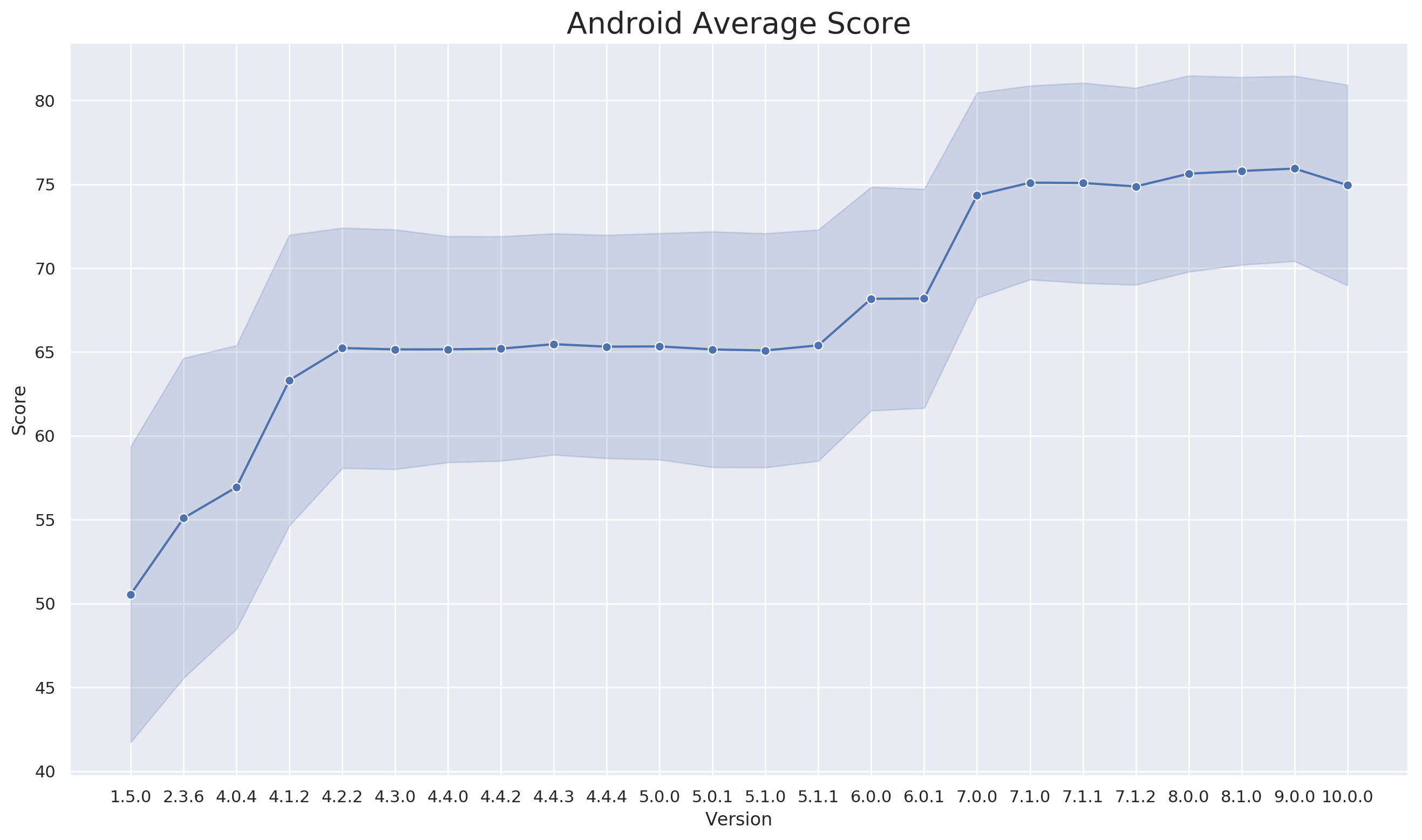

CITL grades products on a score of 0 to 100, where 100 represents the best concievable score. Briefly, these scores reflect the degree to which a given product makes use of basic build hardening features.

We computed these scores for each of the Android releases in our corpus. The results are shown in the following graph:

As we can clearly see, Android has consistently improved their score with each new release. This is great to see!

But the graph can tell us even more. Consider the shaded region, which represents the standard deviation of the per-binary scores for each release.

While each version has some variation in score, the amount of variation is consistent through the lifetime of releases. Higher consistency indicates testing, review, validation or some form of automation that ensures that binaries shipped are uniformly hardened.

Hardening Features Breakdown

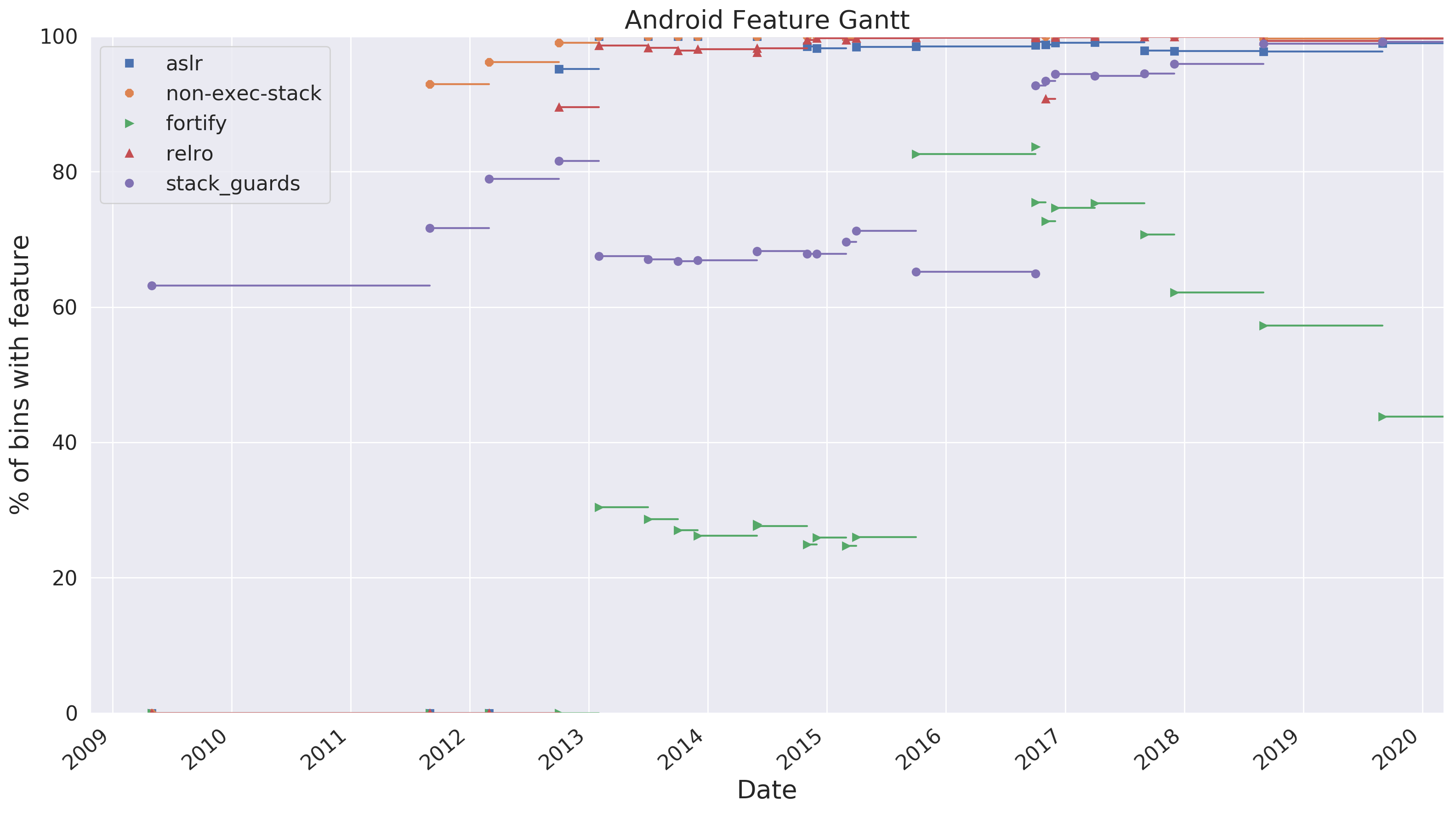

CITL score gives a reasonable approximation of the total hardening. But it is also valuable to break it down into the primary hardening features to see what influences the score.

Here we plot a Gantt chart of each class of hardening feature. Each point represents a release, while each line represents the period of time that version was ‘current’.

(Note: We only were able to select ‘example’ releases from the OEM page, so updates within a version are not captured here.)

In this chart, green represents FORTIFY_SOURCE, the utilization of which jumps around quite a bit. But for all other features shown, utilization clearly has increased over time.

In 2013 in particular, it is obvious that the Android team dedicated time and effort into improving the hardening of the binaries in the base install. This trend continued up to the newest release in our dataset (10.0.0).

Fortify Source

It is interesting to note that ‘fortify source’ does decline in the later releases. In Android 6.0.1, ~83% of the binaries showed some level of fortification. This means that at least 1 function had fortification added in the binary. But by 10.0.0, only 43% of the binaries showed some level of fortification.

This was the only major regression in a hardening feature we could find within the Android lifecycle, so we started to dig in.

Looking at binaries between version 9 and 10, we found that there were a few cases of code being moved from inside a binary to a library. This means the fortifiable functions would be removed and it would drop the binary to a ‘UNKNOWN’ level of fortification. For example, this diff shows a snprintf call that is moved into a library.

However, cases like this do not seem to be the cause of the overall trend. Looking at just those binaries that changed fortification levels between version 9 and 10, we found:

| Increased Fortification | Decreased Fortification |

|---|---|

| 54 | 144 |

Unfortunately we have not been able to find a cause for the overall pattern of decreased fortification. It’s possible the explosion in binary count within those version is a cause but we are still unsure. We leave this as a open question for the community and Android security team.

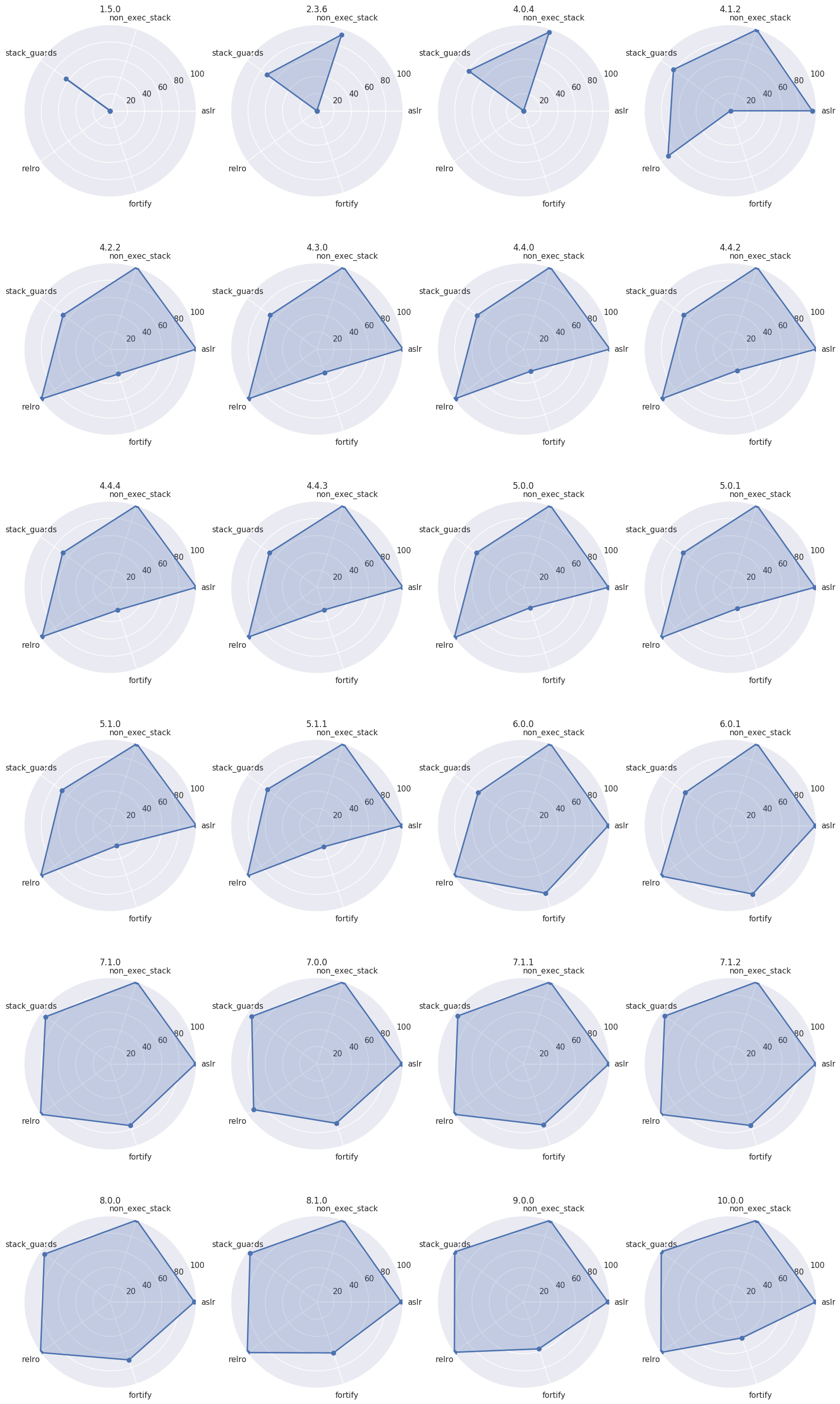

Version Radar Charts

In order to visualize the evolution of hardening coverage in Android, we plotted radar charts for each version. The radar chart places the average (mean) hardening on each radial axis. The more filled in the chart is, the more binaries have hardening features.

Animated:

Here’s each graph individually:

Other Hardening Features

In more recent versions of android we also observed newer hardening feature not mentioned in this post. Things like CFI have been added to some binaries. We are still working on supporting some of these newer hardening features and we plan to revisit this data as our support for these features matures.

Takeaways

Android is a well funded product from one of the largest vendors in the world with billions of users. While it should come as no surprise that Google has invested in hardening their images, we are nonetheless pleased to see these efforts reflected in the data.

We were happy to see such a positive evolution in Android. It provides a productive counter-point to many of the other products we have looked at. Android has continued to push their average hardening scores higher, while also investing in other technologies not reflected in this report (such as sandboxing, CFI, and udsan).

The Data

As with other posts of this nature, we are making our raw data available for others who are interested in performing their own analysis. Below is a link to the raw data on Android:

About the data

Below is a list of columns, their meaning and possible data types.

Some columns optionally have numpy.NaN values. Hardening features are normally expressed as either an integer or a NaN value.

NaN values occur when the given hardening feature isn’t generally applicable to the binary in question. This can occur, for instance, in the case of ELF libaries (.so files), where the ASLR column is NaN because ELF libraries are always relocatable (and thus there is no way for them to not support ASLR).

We invite anyone with questions to reach out to us online.

| Column Name | Data Type | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| sha_hash | str | SHA-256 of input binary |

| filetype | str | File type of the binary: (ELF/PE/MachO) |

| architecture | str | CPU Architecture of the binary: (x86/mips/arm/..) |

| bitness | int | CPU bitness of the binary: (32/64) |

| vendor | str | Vendor name |

| product | str | Product name |

| input_file | str | Binary path within firmware rootfs |

| release_date | str | datetime timestamp (Can be None) |

| firmware_version | str | firmware version |

| norm_score | int | normalized CITL score, range 0 - 100 |

| text_size | int | size of text segment in bytes |

| data_size | int | size of data segment in bytes |

| functions | int | count of functions within analysis CFG |

| blocks | int | count of basic block within analysis CFG |

| is_driver | bool | Is the binary a kernel module |

| is_library | bool | Is the binary a library |

| aslr | int + NaN | Does the binary enable ASLR: NaN (not applicable), 0, 1 |

| non-exec-stack | int + NaN | Does the binary have a non-exec stack: 0, 1 |

| stack_guards | int + NaN | Does the binary enable stack guards: NaN (not applicable), 0, 1 |

| fortify | int + NaN | Does the binary enable fortify source: NAN = None, UNKNOWN_FORT = 0, NOT_FORT = 1, MIXED_FORT = 2, FULL_FORT = 3 |

| relro | int + NaN | Does the binary enable RELRO: NAN = None, NONE = 0, PARTIAL = 1, FULL = 2 |

| seh | int + NaN | Does the binary enable Windows SEH: NaN (not applicable), 0, 1 |

| cfi | int + NaN | Does the binary enable Windows CFI: NaN (not applicable), 0, 1 |

| heap | int + NaN | Does the binary enable the MacOs HEAP protection: NaN (not applicable), 0, 1 |

| extern_funcs_calls | int | Count of external function calls (library calls) within the CFG |

| libs | list | List of linked library |

| good | dict | Dictionary of ‘good’ functions with call counts from CFG: {“my_func”: 2} |

| bad | dict | Dictionary of ‘bad’ functions with call counts from CFG: {“my_func”: 2} |

| risky | dict | Dictionary of ‘risky’ functions with call counts from CFG: {“my_func”: 2} |

| ick | dict | Dictionary of ‘ick’ functions with call counts from CFG: {“my_func”: 2} |